Under canvas – guest post by Tasha Turner

The season of the wildebeest migration in July of 2023 brought me to the rolling plains of Amboseli and the pale-gold grasslands of the Maasai Mara in Kenya, East Africa. A friend with a heart and soul for adventure had fallen in love with Kenya in his early 20s and had since built a life in the Mara, carefully crafting a safari experience for like-minded souls with exclusive boutique safaris.

In 2019, in our own equally remote island home in Far North Queensland Australia, Howard Saunders was visiting with his wife Steph and their two children Oliver and Halina. As so many like-minded adventurers do, Howard struck up a friendship with my parents Anna and Roy.

Upon finishing my law degree at Oxford, I yearned for a change of pace and reached out to Howard with an interest to come and help on his safaris. As Covid cooled and travel picked up again, Howard would be hitting the ground running in the season of 2023, and my passion and experience in cuisine and high-end hospitality would be a welcome addition to his team.

Within half an hour of touching down in Nairobi, one of Howard’s team had whisked me through immigration and sped me to Wilson airport, where domestic and private air travel go through. I met Howard on the tarmac and we took off in his Cessna 182, flying over the Great Rift Valley to his home near the Enonkishu Conservancy. We would spend a few weeks here; For Howard, Naretoi (the 1000 acres which borders Enonkishu) is home. For me, it was a wondrous place to acclimatise, learn my first phrases of Swahili, and get to grips with the complex safaris we had in store.

As the end of June approached, we returned to Nairobi. Nairobi is the beating heart of Kenya and the connective base where the mechanical pieces of a safari are put together. The office of Ker & Downey Safaris, the parent company founded in 1946 and hailed by many as the inventors of the modern-day safari, is situated in the Nairobi suburb of Karen. During the months of June through September, K&D is a bustle of activity as entire mobile camps are carefully planned and packed into enormous trucks, ready to be driven out to remote safari locations. Howard’s is one of only a dozen exclusive safari operators under the legendary K&D name.

From Nairobi and garbed in khaki, I began the long drive out to Amboseli, where we would be spending the first three nights of the trip.

The Amboseli National Park sits on the border of Tanzania. Characterized by its flat and often dry expanses, Amboseli provides a dramatic backdrop for the elephants, wildebeest and zebra which roam its vast plains. The dust swirls and is carried into the atmosphere, creating a whimsical and rather romantic vista. Rolling into Howard’s camp, the looming outline of Kilimanjaro extends up into the sky above us. A few hundred feet away, a large bull elephant walks slowly past the camp, its heels creating silent puffs of dust which eddy in the fading light.

We are met by Mike, Howard’s camp manager, who offers to show me to my guide tent to wash off the dust. My canvas home sits nestled under the shade of a twisting Acacia tree. A small silver basin, filled with inviting fresh water, is propped on a little trivet outside the tent. The ‘windows’ are fly-screen mesh, allowing the breeze to keep the tent cool whilst deterring unwanted insects.

Meanwhile, Howard’s crew are in full motion. His team are a well-oiled machine; together, they work seamlessly to turn the stretch of trees and grassland into a fully-fledged canvas creation.

Camps like Howard’s are the luxurious tip of the East African safari iceberg. Clients can expect a truly personalised, once-in-a-lifetime, guided experience in rustic luxury – and in close proximity to the Kenyan wildlife.

Like the most intricate and elaborate of pop-up cards, Howard’s mobile camp unfolds before my eyes. Tents, furniture, linens and lights spring out of the trucks and into splendid being. By evening, a mess tent, guide tents, a kitchen and the luxurious client accommodation are ready, the latter with colourful bed linens smoothed and flowers arranged neatly by the wash basins.

Walking through camp, and taking care to avoid the vervet monkeys which seem to find visitors most intriguing, Mike offers me a tour of the kitchen. Let me say, just once, that this is perhaps one of the most unique “kitchens” I have laid eyes upon. Two metal-topped tables, made of polished steel, one gas cooker, and the piece de resistance, the “oven” – a hot metal box on which coals are snuggled under and above. This camp kitchen is connected to a small canvas pantry where produce is carefully organised to maintain its freshness. The produce must last until we next make a trip to Nairobi to re-supply.

I pass the first night in my canvas home, listening to the grunting roar of a lion some ways off in the distance. A pearl-spotted owlet hoots from the branch above my tent, like a feathered sentinel. Sound travels far here, over the flat lands of Amboseli, and the nights are filled with activity and intrigue.

The next day, and with the guests arrival by small charter plane, our group is complete.

The day starts early on safari; Woken as the first red rays glow through the mesh of the tent, a tent attendant delivers a thermos of hot milky chai (a deliciously creamy tea made with hot milk instead of water) to your door. Wrapped in warm “shukas” (the traditional colourful shawls of the Maasai) to keep off the morning’s chill, we trundle out of camp before the sun has fully breached the horizon.

Our destination this morning is a nearby Maasai village, where Howard’s close relations with the local Maasai afford his clients a rare peek into the villagers’ extraordinary lives. On route however, our spotter’s eyes detect lion tracks – fresh enough that the dust has not had time to soften the imprints. Our two safari jeeps veer off the path and head into the scrub where the tracks lead.

This thrilling unpredictability, where the mornings and evenings are dictated by the exhilarating and capricious goings on of the wildlife, is what makes the safari so alluring: a lion making a kill of a wildebeest, a cheetah spotted with four cubs, flocks of flamingos taking flight from their aquatic oasis. The cycle of life runs, moment-to-moment, on its own rhythm out here, and for one week with Howard we are lucky enough to experience a part of it.

After our three nights are past, I hug the guests goodbye as they fly off to a lodge in the Borana Conservancy. I will be heading back to Nairobi with the crew for a re-supply, and will meet them in the Maasai Mara National Reserve.

In contrast to Amboseli, the Mara is lush and vibrant in its flora. Big cats (lions, cheetah and leopards) roam the grassy savannah where there are prey in their hundreds. Kiboko Camp, where we are settled, is set on the banks of the Mara river. Thirty feet below us, crocodiles and hippos lazily wallow in the flowing currents.

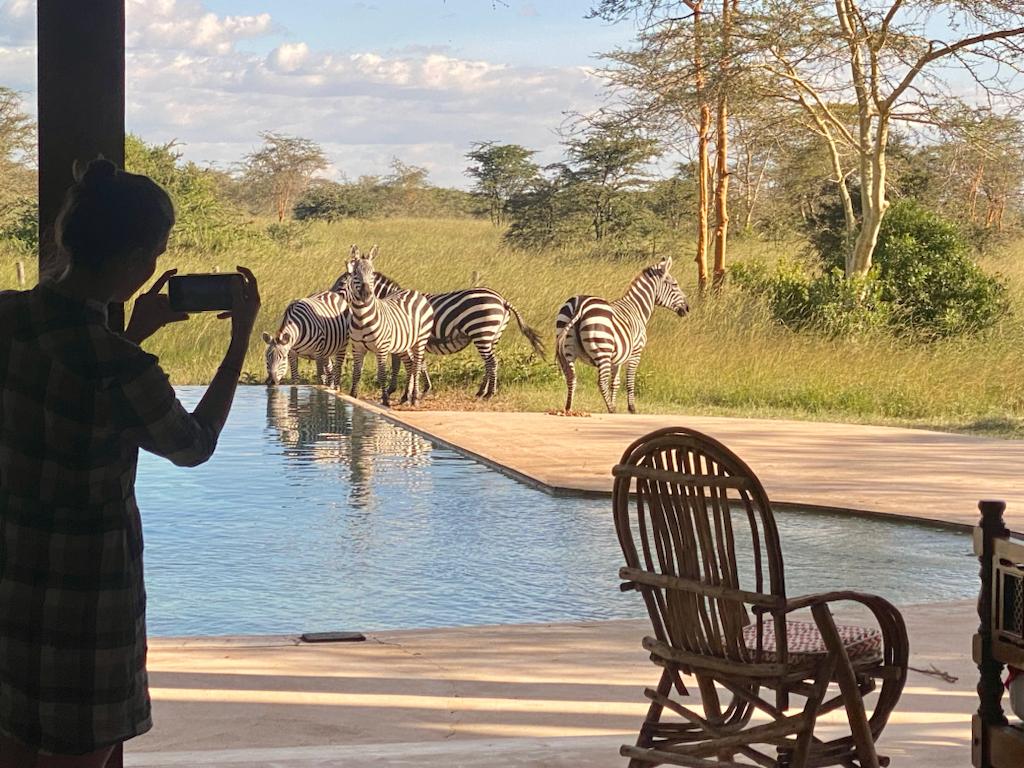

Independent of the extraordinary proximity of wildlife that is so captivating, I found myself both surprised and delighted by the culinary side of Howard’s safaris. Here, meals are memories. After a morning’s game drive, breakfast is often taken under an acacia tree. We are rarely alone in breaking our fast – a herd of almost one hundred zebra and wildebeest graze nearby, intermingled with a family of warthogs who are foraging on bended knee.

In the evenings, clients can wander over to the “mess tent” which has been beautifully lit with hurricane lamps. A long table, clothed in African linen, has been artfully decorated with guineafowl feathers, twisted wood and local flowers gathered from around the camp. Light flickers from candles glowing within large pearly ostrich eggs. We can hear the whoops of hyenas and – disconcertingly close – the trumpet-like grunts of hippos wallowing in the river below.

Dinners are served in our canvas sanctuary. Freshly baked dinner rolls, topped with rolled oats and sesame seeds, are present at every meal. The first course might be a sumptuous spinach and cheese souffle, or a chilled avocado gazpacho. This is then followed by a large cut of beef, marinated in ginger and soy and cooked over the hot coals of the oven. The meals display an artful mastery of fresh spices, honey and herbs. Drawing influences from Indian cuisine, curries are sumptuously seasoned and served with chapati – a flat bread made with flour and oil and lightly fried.

There is an innate and intuitive understanding of heat and gastronomic chemistry which belongs solely to these safari chefs, and in particular to Tom and Anthony. To produce some of the most divine and complex cuisine in difficult conditions, with rudimentary equipment, is an extraordinary feat; To eat their food – a humbling experience.

The end of the safari comes too soon and we all exchange (tearful) goodbyes at the Mara airstrip. There is something here, something in the warmth of the people and in the cool evening air, which captures one’s heart. These stirrings are felt, and not forgotten. One simply has to return to feel it again.